When you picture a rat, what do you see? Fear, disease and destruction? Or maybe, intelligence, cunning and guile? Rats provoke many different responses, but are rarely a welcome presence in our lives. Musophobia, the fear of mice and rats (muso is Latin for mouse), is one of the most common specific phobias around.

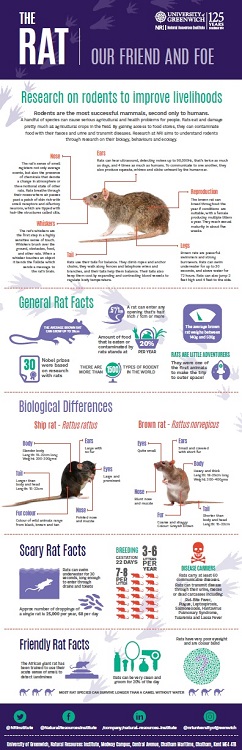

The psychology of this is simple: rodents are the most successful mammals, second only to humans, so perhaps subconsciously we view them as potential rivals to our continued dominance in the world.

Since 2002, rats have enjoyed their own dedicated ‘day’. This year they will be celebrated as a force for good on Thursday 4th April with people rushing to praise their intelligence, loyalty and friendliness and extolling their virtues as pets.

Since 2002, rats have enjoyed their own dedicated ‘day’. This year they will be celebrated as a force for good on Thursday 4th April with people rushing to praise their intelligence, loyalty and friendliness and extolling their virtues as pets.

The Natural Resources Institute carries out huge amounts of research on the ecology and management of rats, in line with its focus on sustainable development to improve livelihoods without harming the environment. Steven Belmain, Professor of Ecology at NRI, recently returned from an Expert Meeting with the World Health Organization in Peru entitled ‘Innovative control approaches for rodent-borne epidemic diseases and other public health consequences of rodents’ proliferation’. With support from the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID),  Professor Belmain is working with the WHO to develop new guidelines and training materials to assist countries to prevent disease outbreaks caused by rats.

Professor Belmain is working with the WHO to develop new guidelines and training materials to assist countries to prevent disease outbreaks caused by rats.

Love or loathe them, rats are undeniably fascinating creatures with many skills and attributes. They can hear ultrasound twice as clearly as dogs and four times better than humans. Their sense of smell is legendary, and they are excellent climbers and swimmers with the ability to squeeze through the tiniest of openings with ease.

Rats are also extremely clean, like cats they spend around 20% of each day grooming themselves and each other. But despite their personal fastidiousness, they are prolific disease carriers, capable of spreading at least 60 infectious diseases which they transmit through their urine, faeces and blood. Even after death they present a real and present danger as their blood can still be transmitted to humans via fleas, flies and ticks.

Brilliant at breeding, a female rat is in theory, capable of producing up to seventeen litters a year. Each litter can comprise ten to twelve babies, so that’s a staggering possibility of a creation of around 200 new little lives, per rat per year. And as each baby rat will reach sexual maturity at about five weeks of age, it’s no wonder we feel threatened by such blatant fecundity.

Brilliant at breeding, a female rat is in theory, capable of producing up to seventeen litters a year. Each litter can comprise ten to twelve babies, so that’s a staggering possibility of a creation of around 200 new little lives, per rat per year. And as each baby rat will reach sexual maturity at about five weeks of age, it’s no wonder we feel threatened by such blatant fecundity.

So-called ‘super-rats’ are frequently in the news. Although resistance to poisons is increasingly common in the UK rat population, the kind of rats found in the UK are actually no bigger than in other countries and remain the same size they always have been. However, newspaper editors know that a ‘super-rat’ headline is guaranteed to shift many copies.

So, are rats simply a dangerous pest to be eradicated, or should we try and harness some of their powers for the good of humanity? Recent reports have shown how the African giant rat has been successfully trained to deploy its acute sense of smell to sniff out landmines, helping to clear land and make it safe again for people to use. These rats are also being used to help diagnose diseases like Tuberculosis as they can smell the TB bacteria in patient sputum samples, rapidly telling their human handlers which samples have TB and which ones do not.

So, are rats simply a dangerous pest to be eradicated, or should we try and harness some of their powers for the good of humanity? Recent reports have shown how the African giant rat has been successfully trained to deploy its acute sense of smell to sniff out landmines, helping to clear land and make it safe again for people to use. These rats are also being used to help diagnose diseases like Tuberculosis as they can smell the TB bacteria in patient sputum samples, rapidly telling their human handlers which samples have TB and which ones do not.

Mice have traditionally always enjoyed good PR – think Tom and Jerry, Mickey Mouse and The Gruffalo to name but a few, but Hollywood took something of a gamble in 2007 by releasing ‘Ratatouille’, an animated children’s film about a cute, clever, sophisticated rat who longs to become a top chef. It won an Academy Award and successfully anthropomorphised rats, breaking box office records around the world, a positive image makeover that rat fans argue was long overdue.

Professor Belmain is currently working on the EcoRodMan https://ecorodman.nri.org/ project in conjunction with a large team of African researches from six countries, to develop new innovations in ecologically-based rodent management. The team is focusing on fertility control and the improvement of ecosystem services to naturally regulate rodent numbers. Rats: heroes or villains? The jury remains out.

Effect of synthetic hormones on reproduction in Mastomys natalensis https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-017-0894-4

Predation by small mammalian carnivores in rural agro-ecosystems: An undervalued ecosystem service? https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.12.006