Every year, air pollution causes up to 36,000 deaths in the UK, making it the “largest environmental health risk we face today”, according to Global Action Plan, the organiser of Clean Air Day 2021. In this piece, NRI’s Dr Conor Walsh, Environmental Scientist and leader of the new BSc (Hons) Climate Change Programme at the University of Greenwich, explores some of his new Programme's key themes on looking for connections within the energy system, coal production and its role in air pollution, carbon capture and energy supply and demand.

During my undergraduate environmental science degree, I remember one particular class where our lecturer asked, ‘which of these fuels is renewable?’ And I was so confident that coal was not renewable. I was a little surprised when our lecturer said it wasn’t so simple: technically coal is formed as part of the slow carbon cycle, whereby carbon in the atmosphere eventually gets stored in sedimentary rock layers and over millions of years (and with heat and pressure) is transformed into coal.

During my undergraduate environmental science degree, I remember one particular class where our lecturer asked, ‘which of these fuels is renewable?’ And I was so confident that coal was not renewable. I was a little surprised when our lecturer said it wasn’t so simple: technically coal is formed as part of the slow carbon cycle, whereby carbon in the atmosphere eventually gets stored in sedimentary rock layers and over millions of years (and with heat and pressure) is transformed into coal.

This occurs naturally, but extremely slowly, over millions of years; therefore, economic demands mean that coal is being extracted at a rate faster than it is being regenerated. This illustrates that we need to think about the mechanism of both supply and demand if we want to understand the environmental impact of consuming different resources.

therefore, economic demands mean that coal is being extracted at a rate faster than it is being regenerated. This illustrates that we need to think about the mechanism of both supply and demand if we want to understand the environmental impact of consuming different resources.

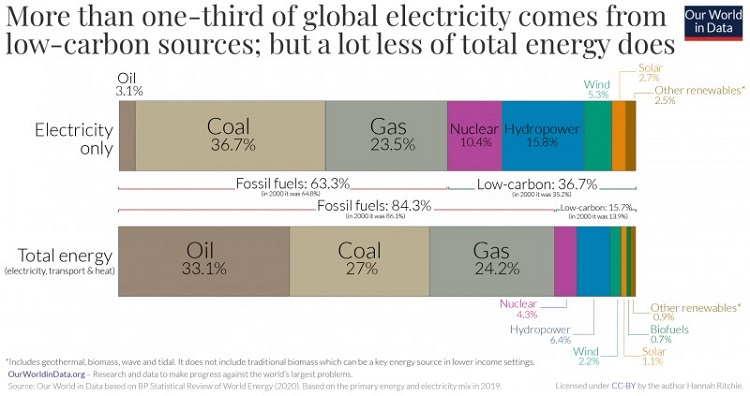

Coal recently returned to headlines following the environmental statement made during the recent G7 summit in Cornwall, as it still currently satisfies 27% of global energy, and 33.79% of electricity demand. Compared with other energy carriers, coal is the single largest contributor to the global electricity mix, but there is a big difference between regions. If you live in France, it is estimated that in 2020, less than 1% of your electricity was produced through coal combustion, in contrast with 23.66% in Germany.

Here in the UK, less than 2% of electricity now comes from coal, a precipitous drop from the 1980s when the UK grid was largely sustained by coal combustion. Sadly, this is not replicated globally; since 1985, the relative proportion of coal in the global electricity mix decreased from 37.93 to 33.79%. Taking sectoral growth into account, the absolute quantity of coal consumed in the electricity sector more than doubled over this period. What we are observing is that industrialised economies are transitioning away from coal whereas key large industrialising economies continue to rely on coal.

So why are we interested in coal from the perspective of climate change?

Firstly, we recognise that the accumulation of carbon in the atmosphere is the main driver of global temperature increase. This April, the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere reached 420 parts per million (ppm) for the first time in human history. This is important as it reflects passing the midpoint between pre-industrial CO2 levels, (approx. 278 ppm), and a doubling of that figure at 556 ppm.

Firstly, we recognise that the accumulation of carbon in the atmosphere is the main driver of global temperature increase. This April, the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere reached 420 parts per million (ppm) for the first time in human history. This is important as it reflects passing the midpoint between pre-industrial CO2 levels, (approx. 278 ppm), and a doubling of that figure at 556 ppm.

Keeping global CO2 concentrations below a 450 ppm threshold is considered essential to avoiding a global average temperature increase of 2ᵒC. The Global Carbon Project estimates that since 1850, coal has added 99 ppm CO2 to the atmosphere, on its own increasing it to 385 ppm, a greater impact than any other fuel. Coal also has one of the highest carbon intensities; the UK Government Green House Gas Conversion Factors for Company Reporting estimate that 1 kWh of energy (on the basis of net calorific value) contained in coal emits 0.33 kg CO2e compared with 0.2 kg CO2e for 1 kWh of fuel energy content for natural gas.

In addition, there is reason to suggest that interplay between coal and climate in large economies has partly been responsible for global emissions increasing in recent years after stagnating in 2015/16 -excluding the impact of the pandemic in reducing emissions, but that’s another story! A 2016 article in the New York Times outlined how drought and increased irrigation demands reduce the water level in hydroelectric dams in China, meaning that coal-fired capacity is needed to meet energy demands, whilst coal power itself consumed significant quantities of water for cooling. This is exacerbated by the fact that globally, many coal-fired power stations are nearing obsolesce/retirement.

How does that bring us back to Cornwall and the G7? There is the view that commitments made are insufficient for rapid emission reduction. The Carbis Bay G7 Summit communiqué reaffirmed “an end to new direct government support for unabated international thermal coal power generation by the end of 2021.” The term unabated is a tricky one – it generally refers to the use of some form of carbon capture and storage, a technology which is still considered unproven at the scale required.

emission reduction. The Carbis Bay G7 Summit communiqué reaffirmed “an end to new direct government support for unabated international thermal coal power generation by the end of 2021.” The term unabated is a tricky one – it generally refers to the use of some form of carbon capture and storage, a technology which is still considered unproven at the scale required.

This means the summit, while making some progress, did not agree on an end date for large-scale coal combustion. The Politico website attributed this to the US administration’s need to avoid specifying policy language that could be interpreted domestically as leading to job losses, as well as to Japan’s continued reliance on coal following the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Ensuring the uptake of new, low-emission technologies compensates for jobs losses is essential is cementing wider support for ambitious climate policies, with agreed end-dates.

These elements highlight the complex interplay between energy supply and demand, and between place and policy, all underpinned by the role of technology. The specific context of each economy will determine the difficulty in transitioning the energy system away from fossil sources. Historically, many industrial countries like the USA, Russia and China have built their economies on their large coal deposits; four countries comprise the majority of global coal reserves: USA (24%), Russia (15%), Australia (14%) and China (13%) [9]. Steel-producing economies such as Japan and China have relied on coal as a source of energy and as an input into integrated steel production.

So where and how energy is produced and consumed is vitally important and can act as a barrier to implementation of the dramatic levels of decarbonisation deemed necessary if we are to avoid exceeding a global average concentration of 450 ppm CO2. Virtually all low emissions scenarios envision an imminent, substantial and sustained reduction in coal, or a commensurate widespread uptake of some form of carbon capture technology. In view of this and considering that global average annual values increased from 401 to 414 ppm between 2015 and 2020, many consider the recent G7 statement to be something of a wasted opportunity.

the dramatic levels of decarbonisation deemed necessary if we are to avoid exceeding a global average concentration of 450 ppm CO2. Virtually all low emissions scenarios envision an imminent, substantial and sustained reduction in coal, or a commensurate widespread uptake of some form of carbon capture technology. In view of this and considering that global average annual values increased from 401 to 414 ppm between 2015 and 2020, many consider the recent G7 statement to be something of a wasted opportunity.

Discussions on the part played by coal in the global carbon challenge, should not lose sight of its role as a source of local area pollution contributing to emissions of particulates and Sulphur Oxide compounds which lead to human health impacts and acidification. The impact of air quality on human health is further highlighted in the UK by marking Clean Air Day, one of the most visible national campaigns advocating for air quality. It is perhaps timely that this year, Clean Air Day is taking place on 17 June, shortly after the G7 commitment and before the forthcoming COP26, also held in the UK.

To find out more about:

BSc (Hons) Climate Change Programme

MSc Global Environmental Change

Carbis Bay G7 Summit Communique document

Coal: global energy and electricity demand

The concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere

UK Government Green House Gas Conversion Factors for Company Reporting: DBEIS DEFRA (2020)