Love your greens? So does the diamondback moth – especially brassicas like broccoli and cauliflower, and leafy salad greens – as many growers around the world know. Despite its diminutive size, the diamondback moth has long been considered a ‘super pest’, especially in the tropics, though a warming climate means it is now venturing into the UK and other locations that are becoming suitable for insects. The diamondback moth’s ability to breed rapidly and develop resistance to pesticides costs growers billions of dollars in control measures and lost produce each year. But it is not unbeatable. NRI experts advise growers that the time is right to get smart about pest management.

‘Business as usual’ pest management?

Traditionally, pest management has been handled by farmers reaching for the most available or the cheapest pesticide to kill a pest. But this technique will not be sustainable with Plutella xylostella, also known as diamondback moth or ‘DBM’, and will aggravate the problem. DBM is extraordinarily good at building up resistance to pesticides: resistance has been reported to almost all pesticides, including those recently introduced, with new modes of action. It can even ‘burn through’ a new pesticide in as little as 18 months. If growers relentlessly use just one kind of pesticide on one pest, they are likely to help that pest build up resistance to the pesticide, thereby reducing the number of chemical solutions available on the shelves. EU legislation supports a gradual decrease in the use of pesticides and limits the variety of pesticides on sale. So what are the options open to growers?![Picture taken by Olaf Leillinger (Own work) [CC BY-SA 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons Plutella.xylostella.7383 750](/images/images/nri-news/2017/Plutella.xylostella.7383-750.jpg)

Smart pest management

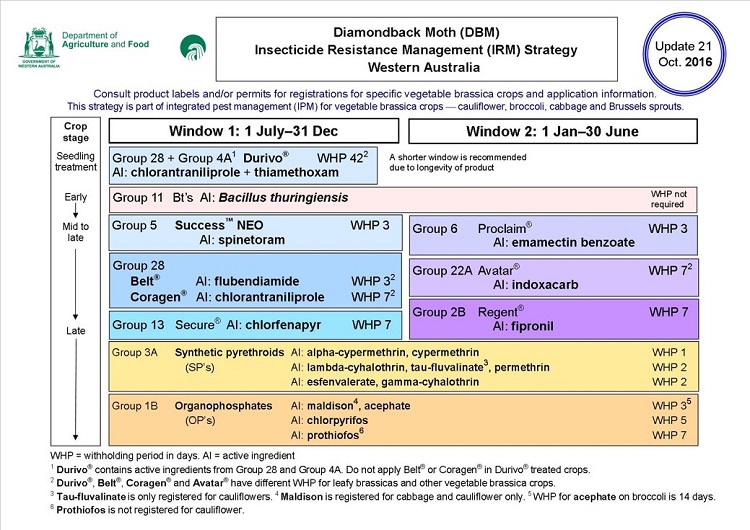

“Growers must practice insect resistance management,” says NRI’s David Grzywacz, specialist in biological crop protection with extensive experience in DBM in the tropics. “This is where farmers use a system of control ‘windows’,” continues David, “in which they rotate insecticides, using different modes of action in a controlled way to prevent building up resistance to any one pesticide. A key to this approach is knowledge of the specific mode of action of each chemical used so that no two chemicals with a similar site of action are used after one another.” This system can integrate chemical pesticides with alternative methods of pest control, such as biopesticides – substances made from natural products or micro-organisms – which are environmentally friendly, biodegradable and leave no harmful residues. This reduces selection pressure on those chemical pesticides that are still effective, prolonging their useful life.

Working with nature

In most places, DBM has important natural predators, such as parasitoid wasps – microscopic insects that lay their eggs inside the eggs, larva or pupa of the moth pest. The wasp kills its host at these different developmental stages, naturally controlling the pest. When pesticides are applied to crops early in the season, the parasitoid wasp is killed instead, virtually creating a ‘happy home’ for the DBM eggs to hatch into pesticide-resistant caterpillars that leave so many holes in brassica leaves they are impossible to sell, or they destroy the crop completely. If growers could use pesticides that don’t affect parasitoids early in the season, the natural enemies are allowed to do their job and the build-up of DBM is delayed. This approach is often built into control windows so that biological or ‘soft’ chemicals are used in early-season control sequences reserving the broad spectrum insecticides for the end of season.

Why now?

Why now?

DBM as a serious pest is relatively new to the UK but it is probably here to stay. Whilst it’s true that numbers of DBM have been recorded in the UK sporadically throughout the last century, the effects of climate change are offering the moth an increasingly hospitable environment in which to stay. Mathematical models based on knowledge of DBM biology clearly predict that the UK is moving towards being a more favourable home for permanent DBM populations. There are reports from growers that small numbers are already ‘overwintering’ in a few places, and this has been confirmed by NRI’s John Colvin, Professor of Entomology, through his studies of brassicas in Kent. This means it’s likely to be a pest of growing importance in the UK – and why we need to plan for it now. There are currently few DBM populations anywhere that have resistance to all pesticides, but importantly, the DBM population discovered in its millions in the UK last summer was found to be resistant to the class of pesticides called pyrethroids – which until recently were the most favoured by growers for pest control in cabbages and similar crops.

The future of smart pest management

The future of smart pest management

“The key to effective insect resistant management is knowledge,” stresses David Grzywacz. “At NRI we have the specialist knowhow, experience and research. It is crucial that farmers and the research community work together to implement a plan to deal with DBM before it becomes a disaster for the brassica industry.”

Links: David gave a talk on this topic at the Brassica and Leafy Salad Conference by the British Growers Association in January 2017.

Articles on DBM control:

- Grzywacz, D., Rossbach, A., Rauf, A., Russell, D.A., Srinivasan, R. and Shelton, A.M., 2010. Current control methods for diamondback moth and other brassica insect pests and the prospects for improved management with lepidopteran-resistant Bt vegetable brassicas in Asia and Africa. Crop Protection, 29(1), pp.68-79.

- Furlong, M.J., Wright, D.J. and Dosdall, L.M., 2013. Diamondback moth ecology and management: problems, progress, and prospects. Annual Review of Entomology, 58, pp.517-541.

- Philips, C.R., Fu, Z., Kuhar, T.P., Shelton, A.M. and Cordero, R.J., 2014. Natural history, ecology, and management of diamondback moth (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae), with emphasis on the United States. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 5(3), pp.D1-D11.

- International Resistance Action Committee The Diamondback Moth, Plutella xylostella:Resistance Management is Key for Sustainable Control

- Lacey, L.A., Grzywacz, D., Shapiro-Ilan, D.I., Frutos, R., Brownbridge, M. and Goettel, M.S., 2015. Insect pathogens as biological control agents: back to the future. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 132, pp.1-41.

- Learmonth S & Lancaster R (2016), Diamondback moth insecticide resistance management in vegetable brassicas: Two-window strategy. Department of Agriculture and Food, Government of Western Australia.