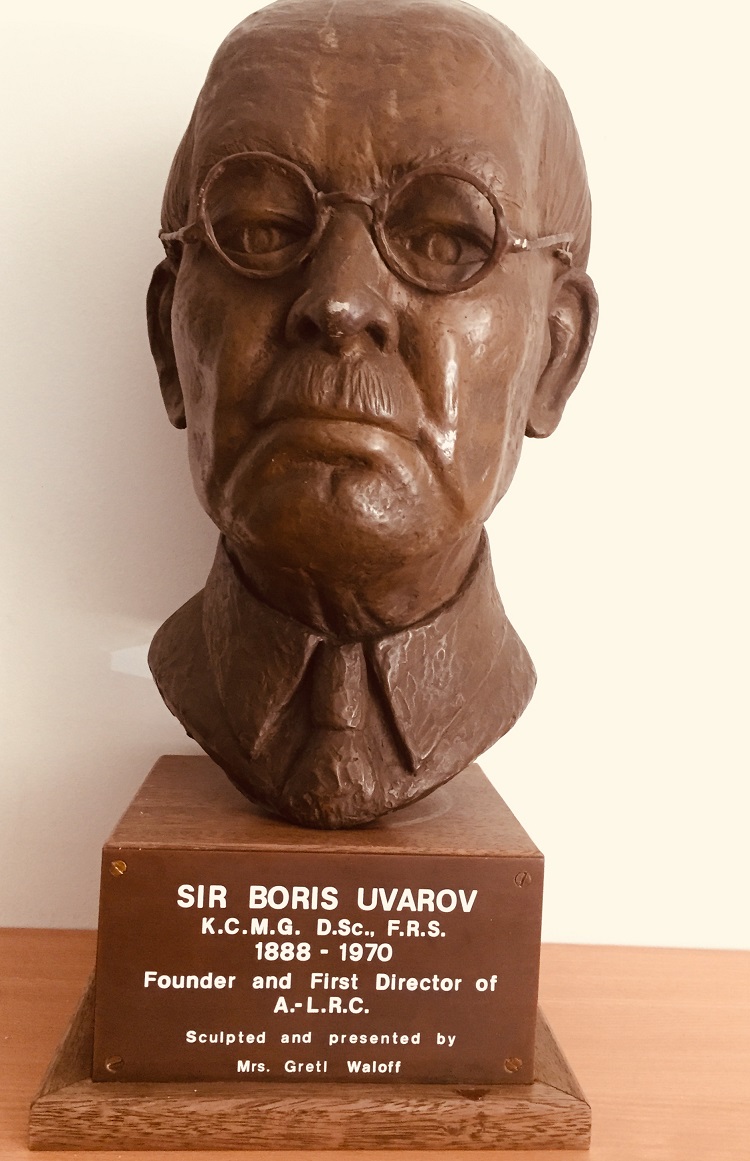

Can you tell the difference between a grasshopper and a locust? The Boris I want to tell you about, (the one now cast in bronze rather than the currently ubiquitous blond one), certainly could. Sir Boris Petrovitch Uvarov KCMG, FRS, the eminent Russian-British acridologist (an expert on locusts and grasshoppers), died nearly half a century ago but the scientific legacy of his important discovery lives on. This is his story.

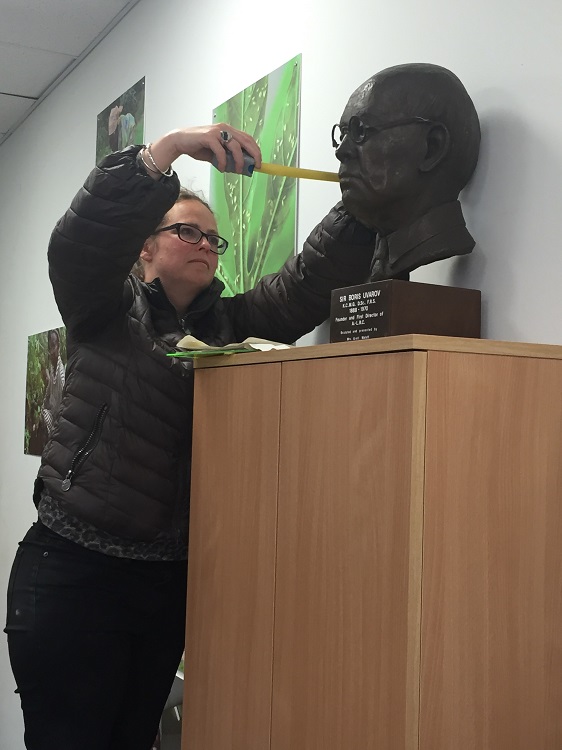

In June, a team from Art UK, a cultural education charity on a mission to capture unknown works of art, came to NRI at the Medway campus of the University of Greenwich to take photographs and detailed measurements of a bust of Sir Boris which sits proudly atop a cabinet in the office of Professor Andrew Westby, NRI’s Director.

In June, a team from Art UK, a cultural education charity on a mission to capture unknown works of art, came to NRI at the Medway campus of the University of Greenwich to take photographs and detailed measurements of a bust of Sir Boris which sits proudly atop a cabinet in the office of Professor Andrew Westby, NRI’s Director.

Sir Boris, or BP as he was known to his associates, was fascinated by locusts. An esteemed entomologist (someone who studies insects), he coined the term ‘acridology’ for the exclusive investigation of locusts and grasshoppers.

Born in 1889 in Uralsk, south-east Russia, Boris’s love of nature came from frequent camping expeditions with his parents and two older brothers. Loading up a horse-drawn wagon, the Uvarovs would disappear for weeks into the wilds, often with the family cat jumping aboard for the ride. Boris enthusiastically collected insects, later winning several school prizes for his efforts.

In 1904 Boris began his university studies at the School of Mining in Ekarterinoslav (now Dnipro in Ukraine), but followed his passion for the natural world by eventually transferring to the Faculty of Biology of the University of St Petersburg.

An engaged student, Boris mingled with the most eminent scientists of the day at the  Russian Entomological Society. By his 30th birthday in 1919, Russia had changed beyond all recognition with the rise of the Bolsheviks, the massacre of the royal family and the catastrophic losses of the First World War. Boris’s position in Tiflis (Georgia) was becoming increasingly dire and to provide an income he had to resort to selling homemade pies in the market square before work.

Russian Entomological Society. By his 30th birthday in 1919, Russia had changed beyond all recognition with the rise of the Bolsheviks, the massacre of the royal family and the catastrophic losses of the First World War. Boris’s position in Tiflis (Georgia) was becoming increasingly dire and to provide an income he had to resort to selling homemade pies in the market square before work.

Good fortune came his way when Patrick A. Buxton, an entomologist stationed with British troops in Georgia, arranged for Boris to travel to London in 1920, to take up an appointment at the Imperial Bureau (later the Commonwealth Institute) of Entomology.

In 1929, Boris, now an established entomologist, was given the task of supervising the investigations into swarming locusts, a much feared and little understood agricultural phenomenon. A single locust swarm can contain billions of insects and travel hundreds of kilometres, destroying all crops in its path.

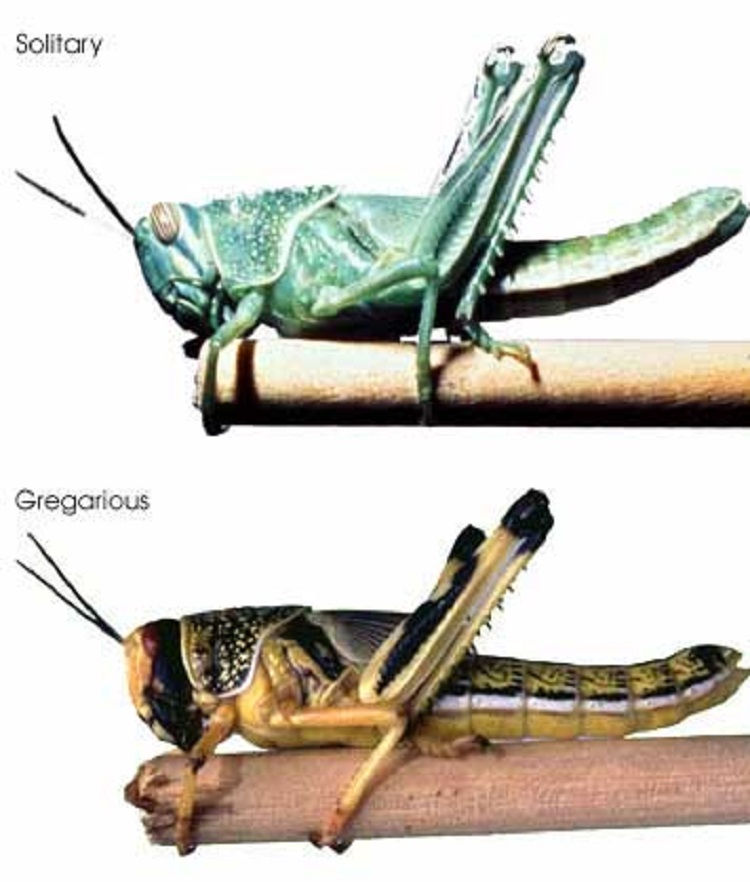

Researchers had long understood that ‘all locusts are grasshoppers, but not all grasshoppers are locusts’, but they failed to understand the crucial link between the two. In fact, the key discovery had been made as early as 1921, when Boris realised that what appeared to be two distinct species, the solitary grasshopper (danica), and the swarming locust (migratoria), were actually one and the same insect, but in different phases. He then worked out how harmless danica morphed into harmful migratoria.

Researchers had long understood that ‘all locusts are grasshoppers, but not all grasshoppers are locusts’, but they failed to understand the crucial link between the two. In fact, the key discovery had been made as early as 1921, when Boris realised that what appeared to be two distinct species, the solitary grasshopper (danica), and the swarming locust (migratoria), were actually one and the same insect, but in different phases. He then worked out how harmless danica morphed into harmful migratoria.

Boris identified a process he called ‘locust phase polyphenism’ whereby an organism can alter its appearance, physiology and behaviour in response to environmental changes. He deduced that the outbreaks of locust plagues happened when the solitary-living grasshoppers were mobbed by groups of gregarious locusts. This crowding caused the grasshoppers to become agitated, grow larger in size and darker in colour. In short, the grasshoppers went from being harmless loners to aggressive ‘gang members’ who liked to swarm, threatening crops and ultimately presenting a serious risk of famine.

Boris convened a series of International Locust Conferences; Rome – 1931, Paris – 1932, Cairo – 1936, Brussels – 1938 and in 1943, London, the same year that he was naturalised and became a British citizen. The outbreak of WWII brought a temporary halt to plans to set up a permanent international organisation in Africa, but Boris kept his hand in by becoming the Locust Control Adviser to the British War Cabinet. At this time, countries in the Middle East and East Africa were being plagued by migratory locusts which threatened strategic food supplies to the Allies.

After the war in 1945, the Anti-Locust Research Centre was established under the Colonial Office, with Boris as Director, leading the way in locust control procedures by helping farmers and furthering international cooperation. Boris put out the call for more information on the breeding habits of grasshoppers; he needed to know if they could be controlled at an early stage, before they learned to swarm.

The answer came in the form of the legendary explorer Wilfred Thesiger who was recruited by O.B. Lean of the Middle East Anti-Locust Unit. Thesiger, tired of his work for the SAS (Special Air Service), enthusiastically took up the challenge to travel through the ‘Empty Quarter’ of the Arabian desert, searching for grasshopper and locust breeding grounds. The photographs that Thesiger took during these expeditions and his map sketches are now preserved with the rest of the historic locust archives at the Natural History Museum in London.

The answer came in the form of the legendary explorer Wilfred Thesiger who was recruited by O.B. Lean of the Middle East Anti-Locust Unit. Thesiger, tired of his work for the SAS (Special Air Service), enthusiastically took up the challenge to travel through the ‘Empty Quarter’ of the Arabian desert, searching for grasshopper and locust breeding grounds. The photographs that Thesiger took during these expeditions and his map sketches are now preserved with the rest of the historic locust archives at the Natural History Museum in London.

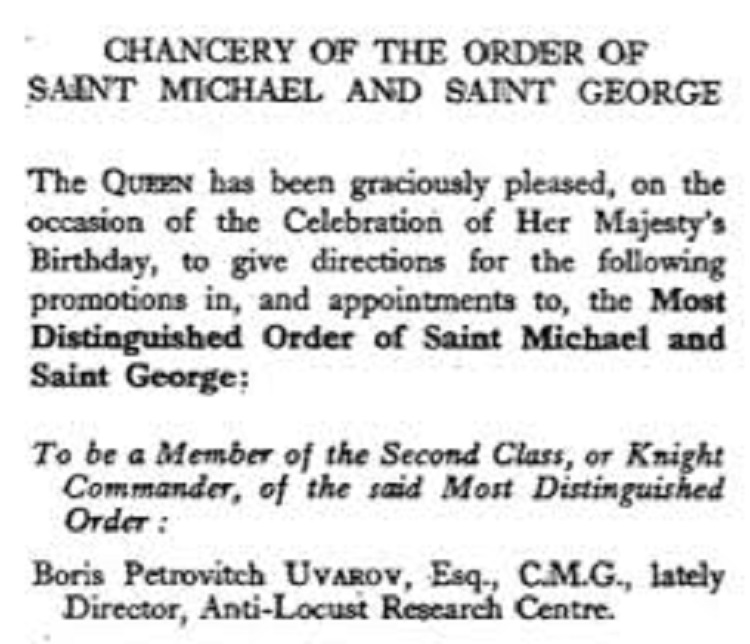

Boris Uvarov retired from the Colonial Office in 1959 but stayed on as a consultant and continued his research on grasshoppers and locusts until his  death in 1970. Sir Boris was unusual; a great scientist and an efficient organiser, he possessed a clear vision of the international cooperation needed to make a difference in the control of migrant pests. He was recognised within his lifetime for his incredible contribution to agriculture and pest control and was made a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in 1943, elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1950 and received a Knighthood to become a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) in 1961.

death in 1970. Sir Boris was unusual; a great scientist and an efficient organiser, he possessed a clear vision of the international cooperation needed to make a difference in the control of migrant pests. He was recognised within his lifetime for his incredible contribution to agriculture and pest control and was made a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in 1943, elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1950 and received a Knighthood to become a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) in 1961.

His meticulously recorded documents and maps are also preserved at the Natural History Museum, and have formed the basis of many biogeographical studies, but his lasting contribution lies in the two volumes of the book “Locusts and Grasshoppers”. Volume 1 was published by Cambridge University Press in 1966, and volume 2 was published posthumously in 1977 by the Centre for Overseas Pest Research. Boris was instrumental in forecasting and planning how to control locusts, and his legacy remains in the important work done by NRI scientists to this day.

His meticulously recorded documents and maps are also preserved at the Natural History Museum, and have formed the basis of many biogeographical studies, but his lasting contribution lies in the two volumes of the book “Locusts and Grasshoppers”. Volume 1 was published by Cambridge University Press in 1966, and volume 2 was published posthumously in 1977 by the Centre for Overseas Pest Research. Boris was instrumental in forecasting and planning how to control locusts, and his legacy remains in the important work done by NRI scientists to this day.

Art UK likes to tell the often fascinating and untold stories behind each piece of art which is what drew them to visit the bust of Boris.

To find out more about:

Opportunities to study pest behaviour & control at NRI